The notion of algorithm is not born with the first computers but well earlier, dating back to Antiquity. As commonly accepted, an algorithm is a set of instructions, a “recipe”, allowing reaching a predefined result. A systematic method can be seen as a synonym for algorithm, i.e. a way to surely reach a fixed goal (and with a finite number of operations). Considering this definition, a cooking recipe can be considered as being an algorithm (and some people are very talented for systematically spoiling their mayonnaise :-)) exactly like the music more played by a barrel organ reading perforated cards.

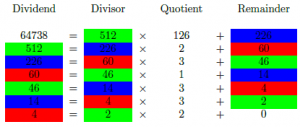

Well known examples of such systematic methods are the Sieve of Eratosthenes which determines the prime numbers smaller than a given N integer (N must obviously not be too big to allow the algorithm to converge in a reasonable time) or the Euclidean algorithm. The Euclidean algorithm (on the left side), which allows finding the Greatest Common Divisor of two integers, is noteworthy in the sense that it is much faster than the algorithm of successive subtractions, which is a method looking more “natural”, which first comes to mind.

Well known examples of such systematic methods are the Sieve of Eratosthenes which determines the prime numbers smaller than a given N integer (N must obviously not be too big to allow the algorithm to converge in a reasonable time) or the Euclidean algorithm. The Euclidean algorithm (on the left side), which allows finding the Greatest Common Divisor of two integers, is noteworthy in the sense that it is much faster than the algorithm of successive subtractions, which is a method looking more “natural”, which first comes to mind.

The notion of algorithm is nowadays strongly linked with computers, these ogres of modern times which devour them without ever being sated. In this regard, it can be noted that French people use the word “informatique” for computer science, as the contraction of “automatic information”, which is a remarkable definition. Since operations performed by computer science are automatic, they rely necessarily on algorithms, which can be as simple as doing additions and subtractions in the case of cash registers (with very often a further refinement: the generation of discount coupons valid for amounts slightly higher than your weekly purchases :-)) or can be very complex when it comes for example to the analysis of data extracted from billions of collisions occurring in particle accelerators.

The speed of an algorithm is an important factor in many cases. It is linked with the notion of real time. For example, the computer system that manages the entrance and exit of subway stations, depending in particular on the zone map, should give its verdict in just a second to ensure the smooth flow of travelers (waiting a minute would be totally unacceptable, causing massive human traffic jams every morning). In the same vein but on a different time scale, the computers forecasting the weather for the next day cannot afford a week of calculation (in this case, engineers adjust forecasting models based on the computing power of machines to be sure to get the results in a timely manner).

To be fast, an algorithm must be pertinent, i.e. it must be optimized. Let’s consider for example chess game. While in this game a human player relies on his experience and intuition (the latter often being unconscious experience), the machine will test a large number of moves by relying on its computing power to try to compete with the human player. The number of possible moves growing exponentially, calculations are optimized by pruning branches leading to situations with no interest. These enhancements, combined with the ever-increasing speed processing, allowed computers to compete with major international chess players and, at the beginning of this century, to beat them systematically.

This latest example shows that the methods deployed in the algorithms can be very different from those developed by human mind, even if, ultimately, the algorithms are (still!) designed by humans. If we push this thought a little bit further, should we not consider that life itself is just a big algorithm, a sequence of commands encoded in the DNA, with the objective of reproducing, at the molecular level, but also at the macroscopic scale, the living beings? Since millennia, bees follow a logic program optimized to ensure the survival of the community of the hive. And we, humans, are we programmed to seek happiness, find our soul mate and make babies with the unconscious objective to ensure the continuity of the human race? If yes, should we still consider ourselves as being free?